BONNEVILLE SALT FLATS, Utah -- For 51 weeks, Roosevelt Lackey refuses to ride his motorcycle. He tunes it in his garage at his farm in Lapeer County. He changes parts. He tests and checks and rechecks every system on the bike, with the help of his best friend and fellow General Motors Corp. retiree, Ken Sperry.

In fact, Lackey, who is 70 and black, and Sperry, who is 60 and white, spend almost every Saturday morning building and rebuilding motorcycles designed to break world speed records.

And they have for decades.

Their children are like brothers, their wives, like sisters.

Never do the former engineers contemplate taking their creations for a spin on the street.

"Too dangerous," Lackey likes to say.

It is an interesting perspective, considering that two weeks ago, on the first morning of Bonneville Speed Week, he rocketed into the white-hot horizon on one of the most inhospitable swaths of land in the United States, attempting to make history.

He was a ghost, a mirage, a blur folded into a machine hurtling down the Salt Flats at 190 m.p.h. Sperry couldn't see him -- nor could anyone else on the team, for that matter. But they knew he was out there. Static-filled voices crackled through the radio.

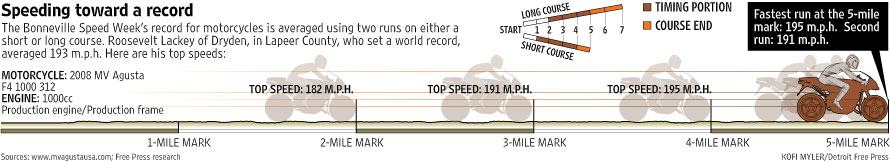

"Quarter-mile: 186.192. ... One mile: 187.724. ... Two mile: 189.822. ... Three mile: 189.983 ..."

By the time Lackey slowed down, he was more than 4 miles away from the start line. Sperry and the rest of their team jumped into trucks and what they call the mule -- an all-terrain vehicle with a motorcycle trailer -- seconds after Lackey took off. Their job was to retrieve Lackey and the bike.

As Sperry and the team closed in on him, Lackey appeared first as a speck on the horizon. A minute later, he began to take human form.

He was kneeling, helmet removed. Sweat slipped down his forehead. It had been nearly 12 months since he rode a motorcycle. Still, he knew in his bones that he hadn't broken a world record.

He stood and began to shed his leather racing suit.

"Sorry, guys," he said when Sperry finally approached.

Sperry shrugged it off. It was the first race. They had the rest of the week to get faster.

Back in the truck, driving to pit row, Lackey felt his adrenaline ease up as the air-conditioning washed over him. "Now I'm OK," he said. "Now I'm OK."

He always liked getting that first run out of the way. His body needed to reacquaint itself with those g-forces, with the catapult into the salty white abyss.

The run down the track had lasted less than 2 minutes. It was the most liberating 2 minutes of his life.

How it all began

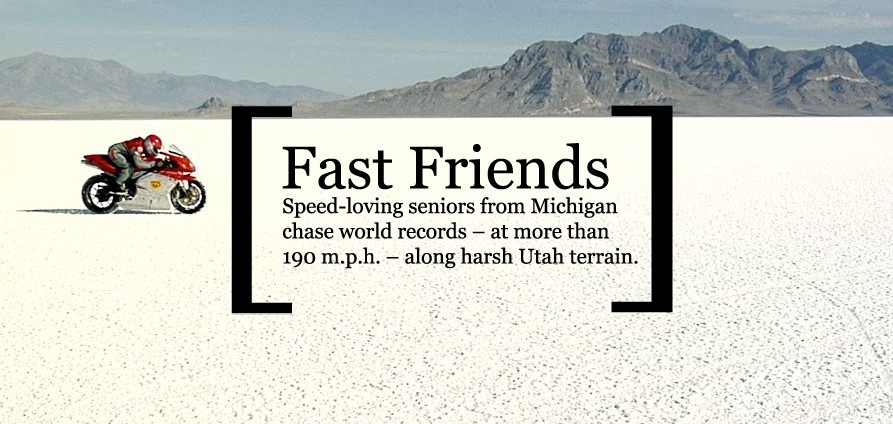

HOW FAST CAN HE GO? With adrenaline pumping, Roosevelt Lackey of Dryden whizzes along a salty track in Utah on Aug. 13 on an MV Agusta signd by workers at the factory. His average speed was 193 m.p.h., but he hit 195 for a world record. (DIANE WEISS/DFP)

Racers, speed-junkies, engineers and mechanics have been chasing immortality on the Salt Flats for almost 100 years. A daredevil topped 140 m.p.h. in 1914 in a Blitzen-Benz. By the late 1940s, the flat, seemingly infinite horizon was drawing speed-seekers from around the world. At Bonneville, a man pushed through 300, 400, 500 and 600 miles an hour, strapped into cars that resembled rockets on wheels.

Eventually, Bonneville Speed Week was born, and for one week every summer, teams racing souped-up cars and motorcycles descend on the flats to see how fast they can go. Three- and 5-mile courses are marked off with orange cones, like construction lanes on an interstate. A volunteer timing association sets the rules -- how vehicles are classified -- and clocks the drivers.

The salty surface turned out to be the perfect track.

Geology made that possible.

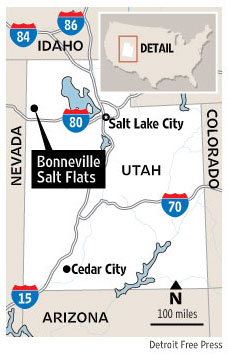

A body of water the size of Lake Michigan once covered much of Utah. Some 15,000 years ago, it spilled into Red Rock pass in Idaho, leaving behind a dreamy, salty, exquisitely flat surface. Even now, Lake Bonneville's old shoreline is etched into the mountains that surround the salt basin, a reminder to drivers that they are racing at the bottom of an inland sea.

"It's humbling," Lackey said.

He has made the cross-country trek from southeastern Michigan since 1969. He is drawn by the scope, the possibility.

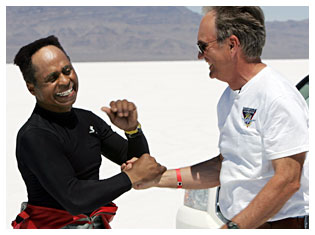

THE KING OF SPEED: Lackey, 70, left, celebrates with Ken Sperry, 60, of Clinton Township, his friend, crew chief and former General Motors work buddy. (DIANE WEISS/DFP)

"Astronauts go to the moon to walk on a surface that looks similar to this," he said. "We can drive 30 hours."

It is a long way from Ecorse, where he grew up and where he bought his first motorcycle -- a Triumph -- at 16. Back then, Rosey, as everyone calls him, rode the streets, navigating Downriver neighborhoods. He rode among the mortals for 25 years, until one day in 1978, when a car pulled in front of him. After that, he swore off all but racetracks and drag strips, man-made or otherwise. The Salt Flats, he said, are "so much safer than riding on the street, it's pathetic."

Lackey met Sperry in the late 1960s. The racer already had owned and sold a gas station in Detroit and worked as a mechanic at a Triumph dealership. Still, he had things to learn about bikes. Sperry, who was only 20 at the time and 10 years younger, had things to teach Lackey, including how to build a fuel injector.

Sperry got his start as a mechanic at a Ford dealership in Highland Park, his hometown. After serving three years in Vietnam, he took a job at a local fuel-injection supply company. In 1972, he went to work at General Motors' Tech Center in Warren. The next year, he told his managers about his buddy.

Sperry and Lackey worked their way into engineering jobs -- back then, you didn't need a college education.

"And it worked out for everybody," Sperry said.

EARLY START: Fans don't like to miss any action on the Salt Flats at Bonneville Speed Week in Utah. Here, spectators hang out and check out the early morning races Aug. 14. (MANDI WRIGHT/DFP)

The combination of Lackey's feel for riding and Sperry's feel for eliciting horsepower quickly turned into victories. Then into records.

Before long, the two of them -- along with a few other locals obsessed with bikes -- were heading to any track they could find. Sometimes, that meant heading south, to places that weren't always so welcoming.

Lackey just ignored it. There was the bike. There was the race. There was Sperry. There was his team. Everything else fell away.

Sperry, however, hated the tension. He remembered one race in Gulfport, Miss.:

"It was tough," he recalled. "They weren't real happy with us. When it looked like we were going to win the race, the promoter of the track came over and said, ... You probably shouldn't stick around for the award ceremony. Just come and see me, and I'll give you the check and trophy, and you can take off.'"

It happened more than once.

Blown engines and budding careers at GM's Tech Center weren't stopping them. Small-mindedness wasn't going to, either.

Adrenaline kicks in, takes hold

MEET THE MV AGUSTA TEAM

ROOSEVELT LACKEY

ROOSEVELT LACKEYAge: 70.

Position: Driver.

Where he lives: Dryden, in Lapeer County.

Where he grew up: Ecorse.

What he does: Retired General Motors engineer.

GARY KOHS

Age: 63.

Position: Owner and sponsor.

Where he lives: Birmingham.

Where he grew up: Northville.

What he does: Owner of Fine Art Models, based in Royal Oak.

KEN SPERRY

Age: 60.

Position: Crew chief.

Where he lives: Clinton Township.

Where he grew up: Highland Park.

What he does: Retired General Motors engineer.

HISTORY OF THE FLATS

The Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah formed when Lake Bonneville, a body of water comparable to Lake Michigan, began evaporating and spilling into the Red Rock pass into Idaho about 15,000 years ago.

The prehistoric Lake Bonneville covered much of North America's great basin region. This included most of present-day Utah.

The salty lake bed left behind stretches of roughly 100 square miles.

Until racing enthusiasts discovered the area, it was known mostly for its harsh climate. The salt flats were named after explorer and fur trapper Benjamin Louis de Bonneville, a French-born officer in the U.S. Army.

Administration of the flats falls to the federal Bureau of Land Management, part of the Department of the Interior.

HOW THE RACE GOT ITS START

In 1896, a cross-country bicycle-race organizer named W..D. Rishel stumbled upon the Bonneville Salt Flats as he mapped out a course from New York to San Francisco.

He convinced Fred Johnson to test-drive his Packard there in 1911. Three years later, he helped bring daredevil Teddy Tezlaff to the flats to race his Blitzen-Benz. Tezlaff set a world record of 141 m.p.h.

By the late 1940s, the Bonneville Salt Flats were luring speed-seekers from around the world. Drivers broke the 300, 400, 500 and 600 m.p.h. barriers at the flats.

Now, for one week every August -- weather permitting -- gearheads descend into the prehistoric salt basin to test the limits of their machines.

By SHAWN WINDSOR

EYES ON THE PRIZE: Roosevelt Lackey -- also known as Rosey -- focuses on the task ahead moments before a race. The Ecorse native is drawn to the salty course because of its scope and possibility. He has made the trek from his home in southeast Michigan since 1969. (DIANE WEISS/DFP)

Over the decades, the racer and the engineer tried all manner of amateur programs -- drag racing, street-racing, land-speed-record racing. They raced half the weeks in a year. But as they got older, the travel and commitment grew cumbersome.

In the late 1990s, they agreed to just do Bonneville. It was only a week. They could convene at Lackey's place in Dryden or Sperry's place in Clinton Township. They would eat breakfast, work at each other's side for a few hours and depart with homework assignments to be completed by the following Saturday.

It was an entire year of calculating and prepping for the Salt Flats. Sperry found it mesmerizing.

"Without the data," he said, "you are just another jerk with an opinion."

The flats demanded problem solving.

"Can you recover?" Sperry said. "In the heat? With no support equipment?"

It was the greatest automotive laboratory in the world, populated by geeks, enthusiasts, gearheads and adrenaline junkies. It was the perfect confluence of plate tectonics and human ingenuity.

"You can just run wide-open and leave it there," Lackey said.

For most of their racing lives, their passion meant building and riding Triumphs. Then serendipity hit last year. And the pair found themselves encamped on pit row next to another adrenaline junkie from back home.

A new plan of attack

Gary Kohs runs a model-making business in Royal Oak. Trains. Planes. Ships. He also collects high-end, high-performance Italian motorcycles. Last year, he took his MV Agusta to the Salt Flats. He wanted a record.

He and his team could barely break 170 m.p.h. As it happened, his pit was next to Lackey and Sperry's. They weren't having a good week, either. They blew two engines. "But they never gave up," Kohs said.

His neighbors used parts from the blown engines to fashion a third. It sputtered and fought them, but managed to get the Triumph down the flats at 150 m.p.h.

Witnessing this, Kohs asked them for help with the Agusta. Sperry suggested adding weight near the seat. The addition worked, and Kohs coaxed 8 miles an hour more from his bike.

After that, Kohs, 63, a whirlwind from Birmingham whose mind turns faster than the crankshaft in his Agusta, decided he had to change his team. He offered Lackey a ride and Sperry the engine and setup. Kohs took care of everything else, including planning and paying for the trip, and emblazoning shirts and hats and coffee cups to help with team chemistry.

Most important, Kohs convinced the president of MV Agusta to give him -- and thus by proxy, Lackey and Sperry -- a new, $25,000 machine to race on the flats.

So what compelled him to turn over his team and equipment to strangers?

"It's about Rosey," he said. "He has this friggin' confidence, this kick-ass ambience. He knows himself. And he's one of the nicest guys you will meet anywhere in the world."

So what compelled him to turn over his team and equipment to strangers?

"It's about Rosey," he said. "He has this friggin' confidence, this kick-ass ambience. He knows himself. And he's one of the nicest guys you will meet anywhere in the world."

Experiencing the extreme

The day before racing opened at Bonneville Speed Week, Sperry didn't drink enough water. Hours of setting up the pit and readying the bikes in the merciless sun and its reflection off the salt sent him to the hospital with heat stroke.

JUBILATION: Teammate Gary Kohs, 63, of Birmingham lifts Lackey, unable to contain his joy over the racer's achievement -- a personal best run of 195.53 m.p.h. on Aug. 13. "He has this friggin' confidence," Kohs says, explaining his admiration. "And he's one of the nicest guys you will ever meet anywhere." (DIANE WEISS/DFP)

"I was a little oozy," he said.

On the morning of the first run, Sperry didn't have much stamina. Lackey, Kohs and the rest of the team tried to fill the void. Lackey took it the hardest.

As the day passed, Sperry slowly regained his strength. The team set a record that afternoon. Race week was falling into place.

By Sunday morning, the second day of racing, Lackey and the team were back in line to break the record they had set Saturday afternoon. They arrived as the sun rose over the mountains.

A couple of hours later, as blue sky settled over the white desert floor, Lackey tucked into the Italian machine and disappeared. For 2 minutes, he heard nothing. He felt nothing. He was floating as the tactile life drifted away.

When he let off the throttle and descended back into full consciousness, he knew he had taken that particular kind of machine where no other man had. He had pushed past 195 m.p.h., a world record for 1000cc stock bikes.

When the team reached him with the official news -- his bike has no speedometer -- he unleashed a primordial yell.

The end of the line

The next night, after a light day of racing -- no other competitor sniffed the record -- Kohs took the team to a shrimp and prime rib buffet in nearby Wendover, a dusty casino and trailer park town that straddles the Utah-Nevada border.

They settled into a casino restaurant lit by neon the color of Pepto Bismol and blue Kool-Aid. Toward the end of the meal, between bites of chocolate cheesecake and banana crème pie, they began recounting the week's highlights, including Rosey's spectacular 195 m.p.h. run.

In only a few days, the guys had collected moments they would share with one another for years. They talked of gears and bores and strokes and horsepower. They talked of speed and heat and tradition. They had come for competition and for car culture and for open spaces.

Every morning, for a week, hundreds of racers and builders lined up to test their theories and their guts. Every night, guys like Lackey, Sperry and Kohs gathered around dining tables to relive the day.

"Everybody is the same out here," Kohs explained.

Everybody who kneels down to run their fingers through the salt feels the same moisture, remnants of a prehistoric lake that stretched to infinity.

"Environmental hell," Sperry said, "but engineering heaven."

A few days after the team had set the record with the 195 m.p.h. run, a competitor on a Suzuki broke it. The team was devastated -- until it began driving east.

By the time we clear Salt Lake City," Sperry said, "we are already talking about next year."